Self-Organizing Learning and Internal Random Excitation as Mechanisms for Imitation and Imagined Action Execution

In a recent video, Pentti Haikonen introduces a compelling new approach to imitation learning—one that does not rely on mirror neurons. Instead, he demonstrates how a machine can imitate motor actions using Haikonen associative neurons, a model that allows imitation to emerge through internal learning processes.

Step 1: From Mental Imagery to Physical Action

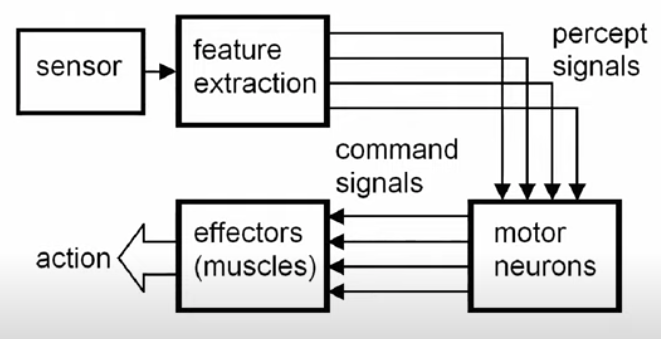

In this demo video, Haikonen highlights a fundamental human ability: we can learn to imitate observed behaviors—such as facial expressions, gestures, or vocal sounds. Even more intriguingly, we can execute actions we have merely imagined, without ever having seen them performed. This involves transforming mental imagery into specific motor commands that control our muscles.

From a cognitive architecture perspective, this transformation requires a link between perceptual signals (what is seen or imagined) and motor output (the control signals sent to muscles). Traditional models invoke mirror neurons to explain this connection, but Haikonen offers an alternative. His system relies on self-organization and internal random excitation, allowing percepts to be associated with motor patterns through learning—without needing pre-coded neuron types dedicated to imitation.

The core challenge is this: which motor neurons should be activated—and in what sequence—to accurately reproduce a perceived action? In other words, how can a system determine the appropriate motor response based solely on sensory input? For imitation to be effective, there must be a reliable mechanism that connects perception and action, enabling the system to translate what it observes into coordinated motor commands. This mapping is not trivial—it requires the system to internally represent both the observed behavior and its own motor capabilities, and to learn how to bridge the two through experience.

Step 2: Random Excitations as a Pathway to Imitation

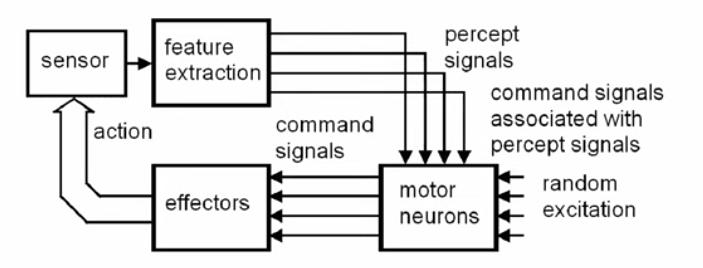

To solve the imitation problem, Haikonen proposes a novel mechanism: internal random excitation of motor neurons. Initially, motor commands are not the result of learned behavior but arise from random internal signals, leading to spontaneous and uncoordinated movements—essentially, exploratory actions.

However, these actions do not go unnoticed. The individual (or system) perceives its own movements through internal sensory feedback—what it sees, feels, or hears as a result of its own action. These sensory impressions (percepts) are then associated with the original random motor commands that caused them.

Over time, the system learns to recognize which motor patterns produce which perceptual outcomes. Through this self-supervised process, a bidirectional mapping is established: from perception to motor command, and vice versa. This mapping enables the system to later reproduce an observed action, not because it has hard-coded mirror neurons, but because it has learned the internal link between what it sees and how to do it.

This approach lays the groundwork for imitation without innate structures, relying instead on learning, feedback, and internal self-organization.

Step 3: From Imagination to Action Through Virtual Perception

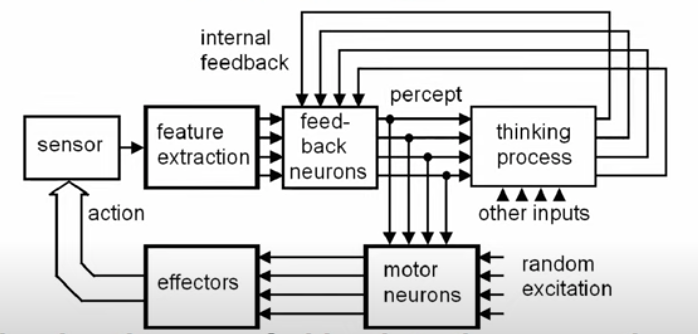

Once the system has established a connection between motor commands and their perceptual outcomes, a powerful new capability emerges: the ability to imagine actions and act on them.

In this step, imagined actions—internally generated representations of movements—can be fed back into the perception system as virtual percepts. In other words, the system simulates the experience of performing an action without actually executing it. This internal simulation triggers the same perceptual-motor associations that were formed during earlier learning through random excitation.

Because the system has already learned which motor commands correspond to which percepts, it can now take an imagined movement (a virtual percept) and translate it into real motor output. In this way, mental imagery becomes executable behavior.

This mechanism mirrors a key aspect of human cognition: we can mentally rehearse actions before we perform them. Athletes visualize movements, musicians imagine playing a piece, and even everyday planning involves simulating potential actions before acting. Haikonen’s model shows how a machine could achieve a similar ability—acting not only on what it sees, but on what it imagines.

Step 4: Hardware Demonstration of the Imitation Principle

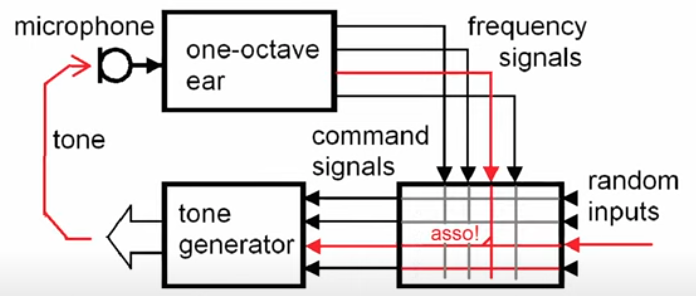

To illustrate this novel approach to imitation, Haikonen presents a compelling hardware demonstration using two custom-built circuit boards, each implementing his Haikonen associative neuron model.

In this setup, one circuit functions as the motor actuator, equipped with a tone generator, while the second acts as the perceptual system, or “artificial ear,” capable of recognizing audio frequencies within a one-octave range.

The process begins with a random input signal sent to the actuator board, which produces a random tone via the tone generator. This tone is then detected by the artificial ear, which converts the sound into a corresponding perceptual signal—effectively simulating how an organism would “hear” its own action.

Crucially, the system then forms an association between the random motor command and the resulting perceived sound. Once this association is learned, hearing the same tone again will trigger the actuator to reproduce it—the perceived becomes the performed. The circuit has, in essence, learned to imitate a tone by linking perception and action through internal association, not through preprogrammed rules or mirrored pathways.

This simple yet elegant demo provides a tangible proof of concept for the broader theory: imitation can emerge from self-organizing, perceptual-motor mappings without relying on traditional mirror neuron frameworks.

It’s becoming clear that with all the brain and consciousness theories out there, the proof will be in the pudding. By this I mean, can any particular theory be used to create a human adult level conscious machine. My bet is on the late Gerald Edelman’s Extended Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. The lead group in robotics based on this theory is the Neurorobotics Lab at UC at Irvine. Dr. Edelman distinguished between primary consciousness, which came first in evolution, and that humans share with other conscious animals, and higher order consciousness, which came to only humans with the acquisition of language. A machine with only primary consciousness will probably have to come first.

What I find special about the TNGS is the Darwin series of automata created at the Neurosciences Institute by Dr. Edelman and his colleagues in the 1990’s and 2000’s. These machines perform in the real world, not in a restricted simulated world, and display convincing physical behavior indicative of higher psychological functions necessary for consciousness, such as perceptual categorization, memory, and learning. They are based on realistic models of the parts of the biological brain that the theory claims subserve these functions. The extended TNGS allows for the emergence of consciousness based only on further evolutionary development of the brain areas responsible for these functions, in a parsimonious way. No other research I’ve encountered is anywhere near as convincing.

I post because on almost every video and article about the brain and consciousness that I encounter, the attitude seems to be that we still know next to nothing about how the brain and consciousness work; that there’s lots of data but no unifying theory. I believe the extended TNGS is that theory. My motivation is to keep that theory in front of the public. And obviously, I consider it the route to a truly conscious machine, primary and higher-order.

My advice to people who want to create a conscious machine is to seriously ground themselves in the extended TNGS and the Darwin automata first, and proceed from there, by applying to Jeff Krichmar’s lab at UC Irvine, possibly. Dr. Edelman’s roadmap to a conscious machine is at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.10461, and here is a video of Jeff Krichmar talking about some of the Darwin automata, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7Uh9phc1Ow